3. Lifecycle

ISBN (Electronic Publication) 978-92-61-42091-8

3. Lifecycle

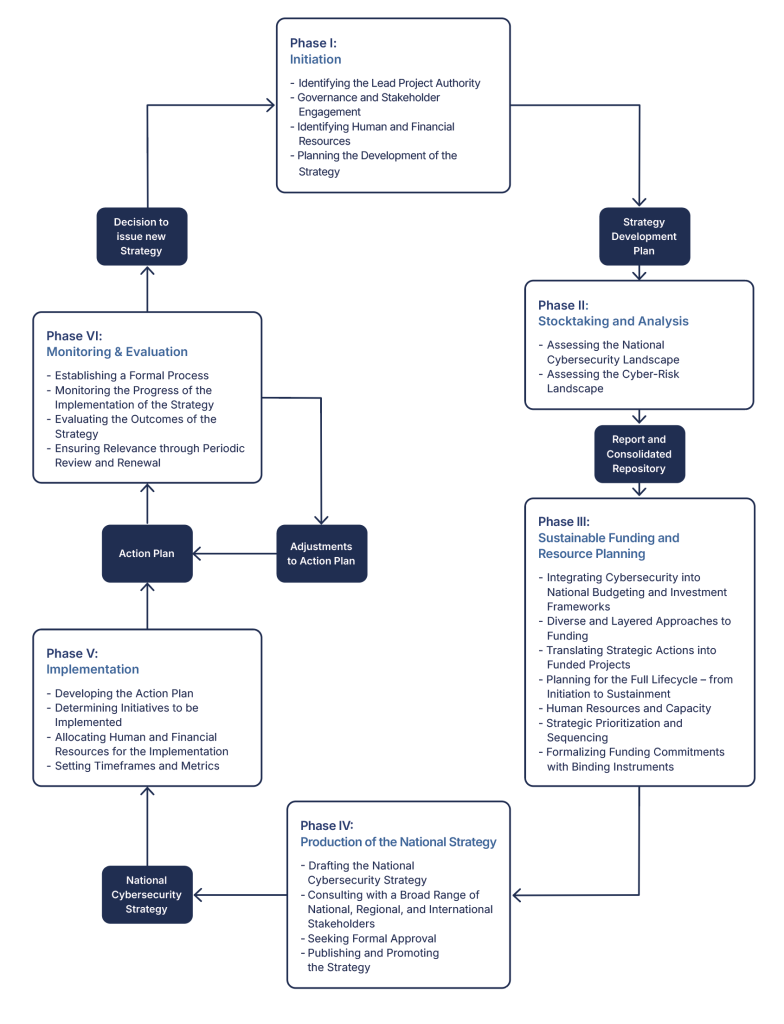

This Section provides an overview of the phases in the development of a National Cybersecurity Strategy, which include:

- Phase I – Initiation

- Phase II – Stocktaking and Analysis

- Phase III – Sustainable Funding and Resource Planning

- Phase IV – Production

- Phase V – Implementation

- Phase VI – Monitoring and Evaluation

It also introduces the key entities that should be involved in the development of the Strategy and highlights other relevant stakeholders that can contribute to the process.

Ultimately, this section aims to help the reader understand the steps a country should take to draft or update a National Cybersecurity Strategy and the possible mechanisms for its implementation, tailored to the country’s specific needs and requirements, integrating the overarching principles (Section 4) and good practice elements (Section 5).

This Lifecycle, as illustrated in Figure 1, guides users of this document in focusing on strategic thinking about cybersecurity and cyber resilience at the national level. This strategic thinking, as explained in Section 2 should take into account and align with the country’s priorities across national security, economic prosperity, and digital resilience, recognizing cybersecurity as an enabler of effective national governance and sustainable development.

Figure 1 – Lifecycle of a National Cybersecurity Strategy

3.1 Phase I – Initiation

The Initiation Phase provides the foundations for effective Strategy development. During this phase, relevant stakeholders in key government entities should establish clear roles and responsibilities, define project management processes and timelines, and identify additional stakeholders who should be involved in the production of the Strategy. It should also be decided whether the document will be a whole-of-nation Strategy or focused primarily on government entities and national critical assets. The outcome of this phase is a development plan for the Strategy, which, where required by national governance processes, may need approval by the country’s Executive.

3.1.1 Identifying the Lead Project Authority

In line with the principle of clear leadership, roles, and resource allocation (Section 4.8), the Strategy development should be coordinated by a single, competent authority. The Executive should appoint a pre-existing or newly created public entity, such as a ministry, agency, or department, to lead the development of the Strategy. This entity, referred to here as the Lead Project Authority, should appoint an individual or team responsible and accountable for leading and coordinating the development process. The designation of a Lead Project Authority does not imply that the entity must oversee a new specific project; it may equally be a ministry, agency, or body with an existing initiative, or simply a political mandate, provided it is formally empowered to coordinate the Strategy’s development.

Where feasible, the Lead Project Authority should be distinct from the entity(ies) responsible for implementation and should be empowered to work impartially with all stakeholders. It should be provided with the tools, resources, and authorities necessary to fulfill its mandate (e.g., authority to convene inter-agency meetings and request information across government) and the capacity to use them effectively.

3.1.2 Governance and Stakeholder Engagement

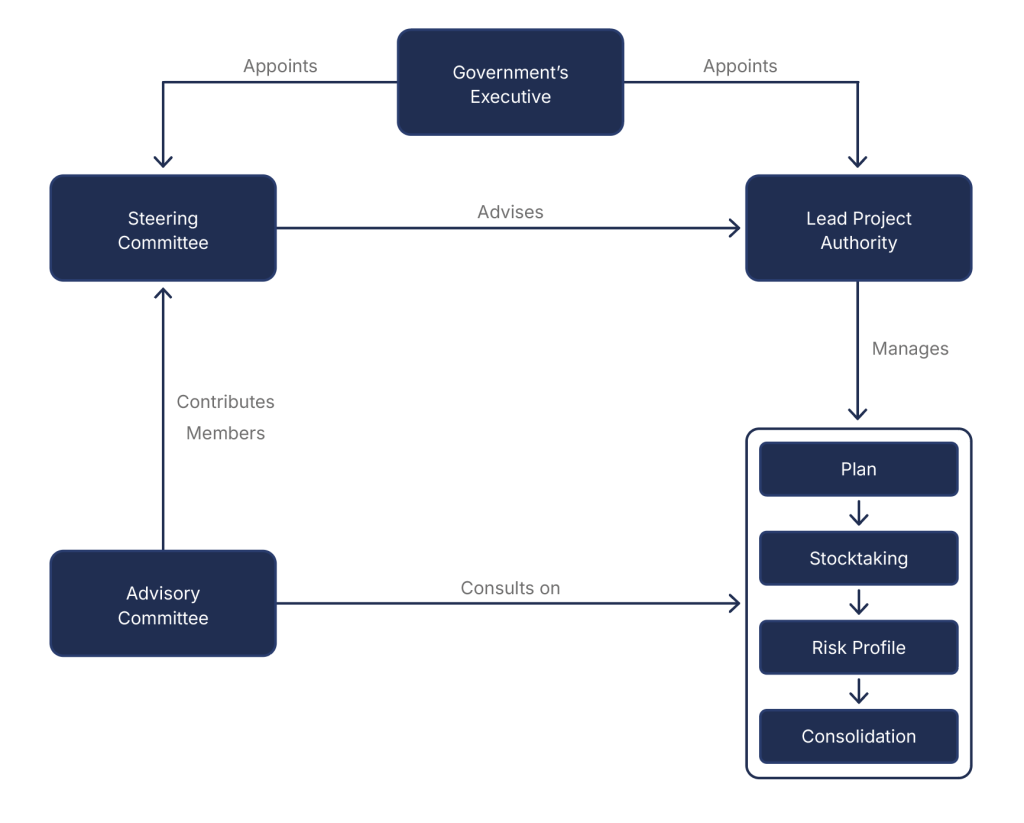

To support the Lead Project Authority in developing the Strategy, the Executive should establish one or more governance mechanisms, such as a Steering Committee for strategic direction and quality assurance, an expert Advisory Group drawing from the public and private sectors and civil society, and formal consultation channels, to ensure transparency and inclusion across the Strategy’s Lifecycle.

The mandate, composition, and operating procedures of these mechanisms should be clearly defined from the outset, with appropriate authorizations for participants who may handle sensitive materials, and membership that reflects assigned responsibilities and seniority where appropriate.

In parallel, the Lead Project Authority should identify an initial set of stakeholders, clarify their roles, and set expectations for collaboration. Priority should be given to: (1) entities with formal policymaking mandates (e.g., ministries, departments, agencies); (2) strategically significant actors (e.g., critical infrastructure owners and operators); and (3) organizations or individuals with demonstrated expertise that can inform the process (e.g., technology and digital service providers, specialized advisers, academic specialists).

As the work progresses, the Lead Project Authority may review and expand the list of relevant stakeholders to incorporate emerging needs and insights from government, the private sector, and civil society, in line with the principle of inclusiveness (Section 4.3).

To enable effective cooperation among stakeholders, the Lead Project Authority should consider regular inter-agency meetings (in-person or virtual), structured engagements with academia and civil society, milestone reviews across the NCS Lifecycle, and periodic progress reports.

Where appropriate, international partners, including international organizations, development agencies, regional bodies, and private entities, can be engaged through expert exchanges and focused working sessions to provide additional support and specialized expertise on the NCS.

3.1.3 Identifying Human and Financial Resources

The Lead Project Authority should identify the human and financial resources needed to develop the Strategy, determine their sources, and outline how they will be procured and allocated. For example, required expertise may be solicited from across government, intergovernmental organizations, the private sector, civil society, or academia.

Funding should draw on a mix of sources, including dedicated national budget lines tied to specific NCS objectives, reallocation or optimization of existing government resources, new budget authorizations, and external investments (e.g., international organizations, multilateral development banks (MDBs), international financial institutions (IFIs), bilateral donors, and philanthropic or technical assistance programs). External actors may provide targeted investments aligned with NCS goals, particularly for cyber capacity-building, infrastructure development, legal and institutional reform, and cybersecurity workforce development.

Depending on national practice, this step may focus exclusively on resourcing Strategy development (with implementation budgeting addressed later in Section 3.3), or the two may be merged. Either way, strategic planning and sustainable resourcing help ensure the NCS is drafted within the planned timeframe, actionable in the near term, and durable over the long term.

Figure 2 – Stakeholders

3.1.4 Planning the Development of the Strategy

In the final step of the Initiation Phase, the Lead Project Authority should prepare a Strategy development plan. Once drafted, it should be submitted to relevant stakeholders (e.g., Steering Committee) for review and to the Executive for approval, in accordance with the national governance processes.

When drafting the development plan, the Lead Project Authority should consider whether the NCS will take the form of legislation or policy, as this may affect the formal processes required and the timeframe for adoption.

The Strategy development plan should clearly identify major steps and activities, key stakeholders, timelines, and resource requirements (human and financial). It should specify how and when relevant stakeholders are expected to participate and provide input and feedback.

Figure 2 illustrates example interactions and role distributions among stakeholders and committees.

3.2 Phase II – Stocktaking and Analysis

The purpose of this phase is to collect information to assess the national cybersecurity landscape and current and emerging cybersecurity risks, to inform drafting and development of the Strategy. The output should be a report providing an overview of the current strategic national cybersecurity posture, risk landscapes, and pressing concerns, to be submitted to key decision-makers.

Before beginning production (or updating) of the Strategy, the Lead Project Authority should carefully analyze and assess the stocktaking results to identify gaps in cybersecurity capacity and present options to address them. The analysis should assess the extent to which existing policy, regulatory, and operational environments meet the national needs, and highlight where they fall short. It should also identify specific issues (e.g., educational and workforce gaps) and define desired outcomes for the Strategy, along with the means available and required to achieve them.

3.2.1 Assessing the National Cybersecurity Landscape

For the Strategy to be effective, it must reflect the country’s cybersecurity posture. An analysis of the existing strengths and weaknesses should therefore be conducted in collaboration with stakeholders across government, the private sector, and civil society. This step follows the principle of a comprehensive approach and tailored priorities (Section 4.2).

The Lead Project Authority should also map stakeholder roles and responsibilities in national cybersecurity to leverage good practices and reduce overlaps.

As part of this effort, the Lead Project Authority should identify assets and services critical to the proper functioning of society and the economy; map existing national laws, regulations, policies, programs, and capacities related to cybersecurity; catalog soft-regulatory mechanisms such as private-public partnerships; and take stock of existing capabilities to address cybersecurity challenges and respond to cyber incidents (e.g., national and sectoral CERTs/CSIRTs/CIRTs and SOCs). The roles and responsibilities of relevant public bodies with cybersecurity responsibilities, such as regulators or data-protection authorities, should also be mapped.

Additionally, data that can inform the national cybersecurity posture should be collected, such as: existing national cybersecurity programs and international initiatives; multilateral and bilateral agreements; private sector projects; digital and cybersecurity-education and skill development programs; cyber-R&D initiatives; indicators on internet penetration, connectivity, and digitalization; and insights on emerging threats and broader cybersecurity trends. Relevant inputs from the private sector, research institutions, and other stakeholder groups should be included in this analysis as well.

For developing countries, mapping collaborative initiatives with development partners is crucial to coordinate technical assistance and investments. The Lead Project Authority should also review relevant information at the regional and international levels, as well as sector-specific strategies and initiatives.

3.2.2 Assessing the Cyber-Risk Landscape

Building on the stocktaking results, the Lead Project Authority should assess risks associated with national digital dependence. This is foundational for prioritizing activities and allocating resources toward the greatest risk-reduction opportunities while avoiding duplication and uneven distribution.

This assessment should begin by identifying national digital assets (public and private), their interdependencies, vulnerabilities, and threats, and estimating the likelihood and potential impact of cyber incidents or disruptions.

This effort aligns with the principle of risk management and resilience (Section 4.6), which recognizes that risk management is critical to fully realizing the benefits of the digital environment for socio-economic development.

This initial risk assessment can serve as the basis for more specific risk assessments in the future (more information on the Principle of Risk Management and Resilience and how to conduct risk assessments can be found in Sections 4.6, 5.2, and 5.3).

3.3 Phase III – Sustainable Funding and Resource Planning

Effective cybersecurity requires sustained commitment, not only in policy and political will, but also in financing. From inception through implementation, evaluation, and renewal, each phase of the Strategy lifecycle demands dedicated, predictable, and long-term funding. Without adequate and continuous financial support, even well-designed strategies risk remaining unrealized. This subsection outlines key considerations for identifying, securing, and managing sustainable funding to support the full lifecycle of the Strategy. All steps should be captured in an Action Plan.

3.3.1 Integrating Cybersecurity into National Budgeting and Investment Frameworks

Ideally, the development and implementation of a Strategy should be resourced through established national budgeting and public investment planning processes. Cybersecurity should not be treated as a siloed or one-time initiative, but as a cross-cutting national priority, integrated and aligned with other strategic investments such as infrastructure development, digital connectivity, public service modernization, and national security.

Cybersecurity-specific funding lines should be reflected in annual budget cycles, medium-term expenditure frameworks, and national development plans, as appropriate. To maximize impact and cost-efficiency, governments should actively seek synergies between the Strategy and other priority sectors. Major national programs in health, education, transportation, or critical infrastructure modernization often have embedded digital and cybersecurity components. Building cybersecurity protections into these programs at the design stage, rather than retrofitting later, can reduce costs, strengthen operational alignment, and improve public trust and mission resilience.

3.3.2 Diverse and Layered Approaches to Funding

Funding a Strategy can and should involve a mix of sources, including:

- Dedicated national budget allocations tied to specific objectives, line-ministry activities, or other key entities with national cybersecurity roles and responsibilities.

- Reallocation or optimization of existing resources, especially where current programs can be enhanced through cybersecurity improvements.

- New budget authorizations or legislation enabling multi-year commitments or authorizing funding for strategic initiatives requiring longer planning horizons than a single budget cycle or administration allows.

- External funding (e.g., international organizations, MDBs/IFIs, bilateral donors, philanthropic or technical assistance programs). These actors may offer targeted financing instruments aligned with strategic goals, particularly for capacity-building, infrastructure development, legal and institutional reform, and cyber/digital workforce development.

Coordination with development partners and inclusion of the Strategy within national development cooperation strategies can ensure that cybersecurity receives appropriate attention within foreign assistance portfolios. Establishing a central coordination mechanism for donor and partner engagement, linked to national cybersecurity priorities, can help avoid duplication, improve absorptive capacity, and align funding with strategic needs.

3.3.3 Translating Strategic Actions into Funded Projects

An additional consideration is the translation of strategic action plans into formal public investment projects using nationally recognized planning and budgeting methodologies. Aligning strategic actions with the country’s public investment management system allows cybersecurity initiatives to be structured as formal projects with clear objectives, indicators, timelines, responsible institutions, and resource requirements.

Governments are encouraged to apply tools such as the Logical Framework Approach (LFA), Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA), Theory of Change (ToC), or similar approaches to assess feasibility, effectiveness, and alignment with national priorities. Embedding these initiatives within national planning and budgeting cycles, such as medium-term expenditure frameworks, helps ensure that cybersecurity efforts are not treated as ad hoc activities, but are sustained, accountable, and integrated into the broader public policy agenda.

3.3.4 Planning for the Full Lifecycle – from Initiation to Sustainment

Sustainable funding must account not only for launching new initiatives, but also for their ongoing operation, maintenance, and renewal. Strategic initiatives often span multiple years and may outlast a particular administration. Budgeting efforts must therefore factor in the full lifecycle costs, including recurring expenditures such as licensing, training, infrastructure maintenance, and staffing. Insufficient planning for sustainment can have serious negative consequences. For instance, deploying a security tool but failing to renew licences or provide ongoing training can create vulnerabilities or degrade trust in digital public services. Similarly, cybersecurity initiatives launched with one-time external funding may not be viable without parallel domestic commitments. The Strategy should therefore:

- Prioritize fewer, fully funded initiatives over many under-resourced ones;

- Build out-year costs into forward-looking budget projections;

- Identify opportunities for cost-sharing or co-financing with development partners, the private sector, or regional initiatives;

- Maintain budget flexibility to address unforeseen costs and emergent needs.

3.3.5 Human Resources and Capacity

A critical, and often underfunded, component of the Strategy is the human element. No strategy can succeed without a capable, well-resourced, and retained cybersecurity workforce. The Strategy should consider human resource needs as a fundamental and recurring line item, not a one-off cost.

Governments should identify common skills needs across ministries and sectors and develop shared training pipelines, career pathways, and professional development programs to maximize efficiency. Investment in workforce development should be treated as a strategic investment, a foundational enabler for nearly every other initiative. Joint investments with regional or international partners in education, training, and certification can help achieve scale, sustainability, and improved outcomes (more information on skills development can be found in Section 5.5).

3.3.6 Strategic Prioritization and Sequencing

Resource planning should be guided by strategic prioritization. Some NCS activities may be high-cost and long-term but deliver outsized benefits; these should be viewed as “strategic investments” and be funded accordingly. The longer an initiative takes to mature, and the more objectives it supports, the more critical it becomes to fully fund it from the outset.

Only a limited number of such initiatives will likely be feasible within available national and partner resources. Governments should therefore carefully sequence implementation based on available funding, political momentum, and institutional readiness, securing early wins that build momentum for subsequent phases.

3.3.7 Formalizing Funding Commitments with Binding Instruments

To ensure the continuity and sustainability of cybersecurity investments, funding and responsibilities for the Strategy implementation should be formalized through binding instruments (e.g., executive mandates, inter-ministerial agreements, cabinet-level resolutions, or legally enacted budgetary provisions). Such instruments establish a formal basis for resource allocation, clarify institutional responsibilities, and protect cybersecurity funding from discretionary budget shifts. Codifying these commitments reinforces political will, strengthens inter-agency coordination, and provides a durable foundation for long-term capacity development and implementation of strategic priorities.

Ultimately, sustained and predictable financing is the backbone of the entire NCS Lifecycle; without it, strategies risk becoming aspirational documents rather than operational drivers of national resilience. Embedding cybersecurity in long-term resource planning ensures that every subsequent phase, from implementation to monitoring, review, and renewal, can deliver tangible, lasting impact.

3.4 Phase IV – Production of the National Cybersecurity Strategy

The purpose of this phase is to develop the text of the Strategy by engaging key stakeholders from the public sector, private sector, academia and civil society through a series of public consultations and working groups. This broader group of stakeholders, coordinated by the Lead Project Authority, will be responsible for defining the overall vision and scope of the Strategy, setting high-level objectives, taking stock of the current situation (detailed in Phase II), prioritizing objectives in terms of impact on society, citizens, and the economy, and available resources (detailed in Phase III). As part of this phase, all cross-cutting principles (Section 4) and good practice elements (Section 5) detailed in this Guide should be considered.

3.4.1 Drafting the National Cybersecurity Strategy

Once the Sustainable Funding and Resource Planning phase is complete, the Lead Project Authority, in collaboration with the Steering Committee, should initiate the drafting of the NCS. While the process can be driven directly by the Lead Project Authority, it is advisable to involve relevant stakeholders to ensure diverse and important perspectives are captured. Dedicated working groups, where feasible and within available resources, may be created to focus on specific topics or draft different sections of the Strategy. These groups should follow the processes established in the Initiation Phase, adjusting them as necessary.

The Strategy should provide the overall cybersecurity direction for the country; express a clear vision and scope; set objectives to be accomplished within a specific timeframe; and prioritize them in terms of impact on society, the economy, and infrastructure. Moreover, it should identify possible courses of action, incentivize implementation efforts, and guide the allocation of required resources to support all these activities. The Strategy may also include findings developed during the Stocktaking and Analysis Phase.

Similar to the step on planning the development of the Strategy, the final document should put forward a clear governance framework (Section 5.1) defining the roles and responsibilities of key stakeholders. This includes identifying the entity responsible and accountable for managing and evaluating the Strategy, as well as the body responsible for its overall management and implementation, such as a central authority or a national cybersecurity council.

The Strategy should also identify the different entities that make up the national cybersecurity architecture of the country, including those responsible for developing cybersecurity policies and regulations; collecting threat and vulnerability information; responding to cyber incidents (e.g., national CERTs/CSIRTs/CIRTs); and strengthening preparedness and crisis management. It should clearly describe how these entities interact with each other and with the central authority.

3.4.2 Consulting with a broad range of national, regional, and international stakeholders

As mentioned above, stakeholder engagement is crucial for the success of a Strategy. To ensure that the final document is based on a shared vision and minimizes the risk of inconsistent or conflicting requirements with other national ones, the draft should be disseminated widely, including stakeholders beyond those directly involved in the Strategy development process. This can be done through a variety of engagements, including online consultations, validation workshops, and additional working groups. International and regional organizations and other external stakeholders can also play a role by providing advice and expertise. Feedback and comments from this process should be incorporated into the final Strategy.

3.4.3 Seeking formal approval

In the final step, the Lead Project Authority should ensure that the Strategy is formally adopted by the Executive. This adoption process will vary by country and depend on the legislative framework. For example, adoption could take place through a parliamentary procedure or a high-level administrative document of the government, such as a decree or a resolution.

Furthermore, it is essential that the Strategy is not only approved at the highest levels of government, but that this commitment carries through into the implementation phase. The relevant entities and officials should be held accountable and supported with both political capital and resources, ensuring that cybersecurity efforts remain strong and sustainable over time, beyond the initial publication of the Strategy.

3.4.4 Publishing and promoting the Strategy

The Strategy should be a public document and made readily available. The launch of the Strategy should ideally be accompanied by internal and external promotional activities. Broad dissemination of the Strategy will ensure that the public is aware of the government’s cybersecurity priorities and objectives and will support national awareness-raising efforts.

The accompanying Action Plan, whether annexed to the Strategy or published separately, should also highlight opportunities for further engagement and cooperation with all relevant stakeholders.

3.5 Phase V: Implementation

A structured approach to implementation, supported by adequate human and financial resources (see also Section 3.3), is critical to the success of the Strategy and should be considered as part of its development. In this context, adequate human resources refers to the availability of sufficient staff and professionals with expertise in governance, policy, cybersecurity, technology, and regulatory matters. The implementation phase is often centered on an Action Plan, which guides the activities envisioned.

3.5.1 Developing the Action Plan

As with the development of the Strategy, its implementation cannot be the sole responsibility of a single body or authority. Instead, it requires engagement and coordination of a range of stakeholders across government, with additional support from critical infrastructure owners and operators, civil society, and the private sector. The Action Plan, developed in line with the principle of clear leadership, roles, and resource allocation (Section 4.8), provides the framework for effective implementation.

The process of developing the Action Plan is nearly as important as the document itself. Orchestrated by the Lead Project Authority, it should serve as a mechanism to bring relevant stakeholders together to agree on objectives and outcomes, coordinate efforts, and pool resources.

3.5.2 Determining initiatives to be implemented

The Strategy defines the government’s objectives and the outcomes it seeks across different focus areas. In the Action Plan, the Lead Project Authority, in coordination with relevant stakeholders, should identify the specific initiatives that will achieve these objectives. Examples include organizing cybersecurity exercises and drills, establishing security baselines for critical infrastructure sectors, and setting an incident reporting framework, among others.

The timeline and effort needed for the implementation of these initiatives should be prioritized according to criticality, ensuring that limited resources are leveraged effectively. To this end, results from Phase II (Stocktaking and Analysis), especially the assessment of the cybersecurity risk landscape (Section 3.2.2), should inform prioritization.

3.5.3 Allocating human and financial resources for the implementation

Once initiatives are prioritized, they should be formalized within the Strategy and/or the Action Plan, which should identify the specific entities responsible and accountable for each initiative (e.g., ministries, departments, agencies). These entities are then accountable for the implementation of each specific initiative assigned to them and are expected to coordinate their efforts with other relevant stakeholders as part of the implementation process.

The Lead Project Authority should ensure these entities have the appropriate legal or institutional mandate to carry out their tasks. It should also work with them to determine the human, technical, and financial resources required to accomplish the work (e.g., expertise, staffing, funding needs). The Lead Project Authority should help identify and secure the required resources in line with Phase III (Section 3.3).

3.5.4 Setting timeframes and metrics

A critical element of the Action Plan is the development of specific metrics and key performance indicators (KPIs) to track implementation and assess progress of each initiative laid out in the Action Plan (see also Section 3.6). These may include the percentage of actions completed, budget disbursement to date, or identification of entities falling behind on delivery, etc. Specific timelines for the implementation of each initiative should also be clearly set.

The Lead Project Authority, in partnership with the implementing entities, should develop these metrics and KPIs. Implementing entities should also maintain a more detailed set of metrics to support evaluations of efficiency and effectiveness during and after their completion.

3.6 Phase VI – Monitoring and Evaluation

Developing and implementing the Strategy is an ongoing process. A competent authority should devise a formal process to monitor and evaluate the Strategy. During the monitoring phase, the government should ensure that the Strategy is implemented in accordance with its Action Plan. During the evaluation phase, the government and the national competent authority should assess whether the Strategy remains relevant in light of the evolving risk environment, whether it continues to reflect government objectives, and what adjustments may be necessary.

3.6.1 Establishing a formal process

To ensure effective monitoring and evaluation of the Strategy implementation, the government should identify an independent entity responsible for monitoring progress and assessing efficacy. This entity should ideally be involved in defining appropriate monitoring and evaluation metrics for the Strategy and its Action Plan during the Production and Initiation phases.

Monitoring and measuring the performance and execution of the Action Plan should be embedded in the governance mechanisms the country establishes for the Strategy. Continuous assessment of implementation progress (i.e., what is working and what is not) helps inform adjustments. Good governance mechanisms should also clearly delineate accountability and responsibility for successful execution. Establishing metrics or KPIs by near-term, mid-term, and long-term objectives helps reinforce governance and management structures.

Key performance indicators or metrics should be SMART:

- Specific – target a defined area for improvement and focus on the change expected.

- Measurable – quantify or suggest clear indicators of progress.

- Achievable – state what results can realistically be achieved with available resources.

- Relevant – focus on significant indicators of progress and specify who is responsible.

- Time-related – specify when the result(s) are expected.

KPIs should always be tailored to specific goals and linked to specific initiatives to facilitate corrective actions. The more detailed a KPI is, the more difficult it will be to measure reliably, so balance is required. Baseline metrics are essential for effective monitoring and for identifying areas of improvement. Budget allocation should also reflect the ambition and complexity of the intended impact.

3.6.2 Monitoring the progress of the implementation of the Strategy

The entity responsible for monitoring the progress of implementation of the Strategy should do so according to an agreed timeline across the entire lifecycle of the Strategy. Monitoring outputs (e.g., reports) should highlight deviations from the agreed evaluation parameters (e.g., deadlines, quality standards, expenditures, etc.) and provide explanations for delays, such as shifting priorities, insufficient staffing or resources, etc.

This should complement periodic updates from initiative owners to the Lead Project Authority. All relevant stakeholders should be actively involved in monitoring the implementation and progress of the Strategy. This approach ensures accountability for commitments, facilitates early identification of challenges, and enables the government to take corrective action or adapt Action Plans based on lessons learned during the implementation process.

3.6.3 Evaluating the outcomes of the Strategy

Beyond tracking progress, it is also essential to periodically evaluate outcomes against the objectives originally set. This evaluation determines whether the objectives of the Strategy are being achieved or whether adjustments are needed.

As part of this process, the broader digital and cybersecurity risk environment must also be regularly re-evaluated to determine whether external changes are affecting the outcomes of the Strategy. Effectively, this process acts as a light-touch revision of a country’s risk assessment profile.

The assessment, together with associated recommendations, should be compiled into a report for the Lead Project Authority. This report should include proposals to update the Action Plan and ensure that it remains current and responsive to evolving policies, national cybersecurity architecture, and the risk landscape.

Ultimately, reports produced throughout the NCS lifecycle should serve as the basis for the overall review of the Strategy, in line with the timeline set during the Initiation phase. This overarching review should assess not only progress and external developments, but also shifts in government priorities and objectives.

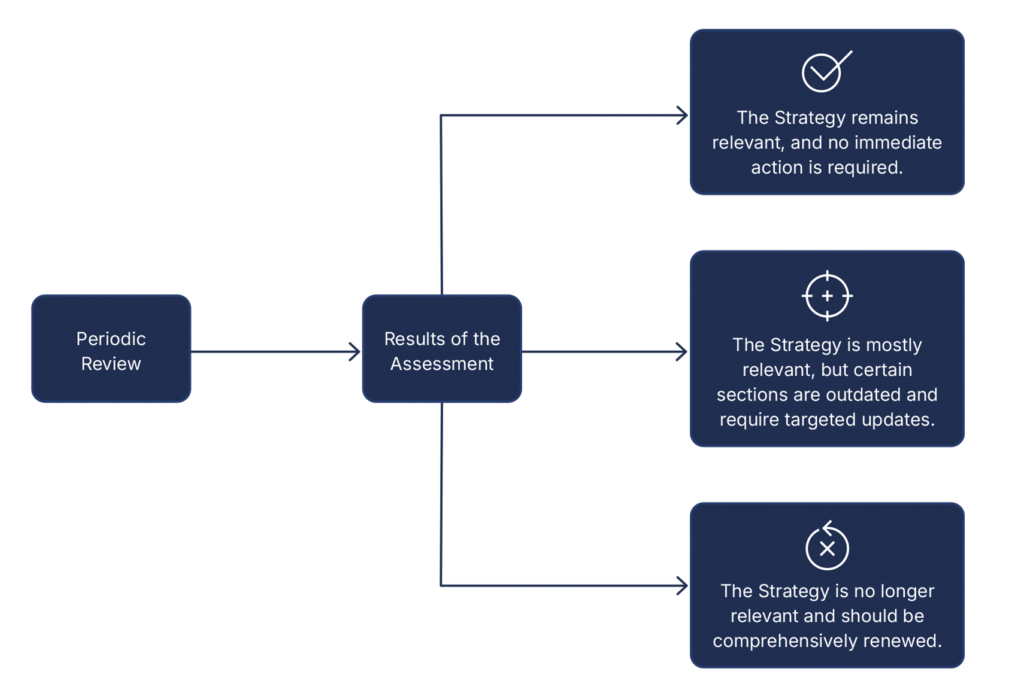

3.6.4 Ensuring Relevance through Periodic Review and Renewal

The Strategy should be subject to regular review to ensure it remains aligned with evolving threats, technological changes, and shifting national priorities. Reviews should be institutionalized in the governance framework, include (where possible) the involvement of external stakeholders who can provide alternative viewpoints, and be scheduled at regular intervals (e.g., every 3 to 5 years), with at least one mid-term review conducted halfway through the Strategy’s expected lifespan. In addition, reviews should be triggered by major events such as significant cyber incidents, legislative or regulatory changes, or shifts in the geopolitical landscape.

The review process should assess the continued relevance of the Strategy and produce recommendations for how to move forward. For instance, this may include:

- The Strategy remains relevant, and no immediate action is required.

- The Strategy is mostly relevant, but certain sections are outdated and require targeted updates.

- The Strategy is no longer relevant and should be comprehensively renewed.

Ultimately, regular and mid-term reviews ensure that the Strategy remains a living document, responsive to changing conditions. These reviews should feed directly into the next cycle of NCS development, beginning again with initiation and stocktaking.